| |

A solar cell (also called a photovoltaic cell) is an electrical device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by the photovoltaic effect. It is a form of photoelectric cell (in that its electrical characteristics—e.g. current, voltage, or resistance—vary when light is incident upon it) which, when exposed to light, can generate and support an electric current without being attached to any external voltage source, but do require an external load for power consumption.

The term "photovoltaic" comes from the Greek φῶς (phōs) meaning "light", and from "volt", the unit of electro-motive force, the volt, which in turn comes from the last name of the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta, inventor of the battery (electrochemical cell). The term "photo-voltaic" has been in use in English since 1849.

Photovoltaics is the field of technology and research related to the practical application of photovoltaic cells in producing electricity from light, though it is often used specifically to refer to the generation of electricity from sunlight. Cells can be described as photovoltaic even when the light source is not necessarily sunlight (lamplight, artificial light, etc.). In such cases the cell is sometimes used as a photodetector (for example infrared detectors), detecting light or other electromagnetic radiation near the visible range, or measuring light intensity.

The operation of a photovoltaic (PV) cell requires 3 basic attributes:

1.The absorption of light, generating either electron-hole pairs or excitons.

2.The separation of charge carriers of opposite types.

3.The separate extraction of those carriers to an external circuit.

In contrast, a solar thermal collector supplies heat by absorbing sunlight, for the purpose of either direct heating or indirect electrical power generation. "Photoelectrolytic cell" (photoelectrochemical cell), on the other hand, refers either to a type of photovoltaic cell (like that developed by A.E. Becquerel and modern dye-sensitized solar cells), or to a device that splits water directly into hydrogen and oxygen using only solar illumination.

History

The photovoltaic effect was first experimentally demonstrated by French physicist A. E. Becquerel. In 1839, at age 19, experimenting in his father's laboratory, he built the world's first photovoltaic cell. Willoughby Smith first described the "Effect of Light on Selenium during the passage of an Electric Current" in an article that was published in the 20 February 1873 issue of Nature. However, it was not until 1883 that the first solid state photovoltaic cell was built, by Charles Fritts, who coated the semiconductor selenium with an extremely thin layer of gold to form the junctions. The device was only around 1% efficient. In 1888 Russian physicist Aleksandr Stoletov built the first cell based on the outer photoelectric effect discovered by Heinrich Hertz earlier in 1887.

Albert Einstein explained the underlying mechanism of light instigated carrier excitation—the photoelectric effect—in 1905, for which he received the Nobel prize in Physics in 1921. Russell Ohl patented the modern junction semiconductor solar cell in 1946, which was discovered while working on the series of advances that would lead to the transistor.

The first practical photovoltaic cell was developed in 1954 at Bell Laboratories by Daryl Chapin, Calvin Souther Fuller and Gerald Pearson. They used a diffused silicon p–n junction that reached 6% efficiency, compared to the selenium cells that found it difficult to reach 0.5%. Les Hoffman CEO of Hoffman Electronics Corporation had his Semiconductor Division pioneer the fabrication and mass production of solar cells. From 1954 to 1960 Hoffman improved the efficiency of Solar Cells from 2% to 14%. At first, cells were developed for toys and other minor uses, as the cost of the electricity they produced was very high; in relative terms, a cell that produced 1 watt of electrical power in bright sunlight cost about $250, comparing to $2 to $3 per watt for a coal plant.

Solar cells were brought from obscurity by the suggestion to add them, probably due to the successes made by Hoffman Electronics, to the Vanguard I satellite, launched in 1958. In the original plans, the satellite would be powered only by battery, and last a short time while this ran down. By adding cells to the outside of the body, the mission time could be extended with no major changes to the spacecraft or its power systems. In 1959 the United States launched Explorer 6. It featured large solar arrays resembling wings, which became a common feature in future satellites. These arrays consisted of 9600 Hoffman solar cells. There was some skepticism at first, but in practice the cells proved to be a huge success, and solar cells were quickly designed into many new satellites, notably Bell's own Telstar.

Improvements were slow over the next two decades, and the only widespread use was in space applications where their power-to-weight ratio was higher than any competing technology. However, this success was also the reason for slow progress; space users were willing to pay anything for the best possible cells, there was no reason to invest in lower-cost solutions if this would reduce efficiency. Instead, the price of cells was determined largely by the semiconductor industry; their move to integrated circuits in the 1960s led to the availability of larger boules at lower relative prices. As their price fell, the price of the resulting cells did as well. However these effects were limited, and by 1971 cell costs were estimated to be $100 per watt. Efficiency

Solar panels on the International Space Station absorb light from both sides. These Bifacial cells are more efficient and operate at lower temperature than single sided equivalents.The efficiency of a solar cell may be broken down into reflectance efficiency, thermodynamic efficiency, charge carrier separation efficiency and conductive efficiency. The overall efficiency is the product of all of these individual efficiencies.

A solar cell usually has a voltage dependent efficiency curve, temperature coefficients, and shadow angles.

Due to the difficulty in measuring these parameters directly, other parameters are measured instead: thermodynamic efficiency, quantum efficiency, integrated quantum efficiency, VOC ratio, and fill factor. Reflectance losses are a portion of the quantum efficiency under "external quantum efficiency". Recombination losses make up a portion of the quantum efficiency, VOC ratio, and fill factor. Resistive losses are predominantly categorized under fill factor, but also make up minor portions of the quantum efficiency, VOC ratio.

The fill factor is defined as the ratio of the actual maximum obtainable power to the product of the open circuit voltage and short circuit current. This is a key parameter in evaluating the performance of solar cells. Typical commercial solar cells have a fill factor > 0.70. Grade B cells have a fill factor usually between 0.4 to 0.7. Cells with a high fill factor have a low equivalent series resistance and a high equivalent shunt resistance, so less of the current produced by the cell is dissipated in internal losses.

Single p–n junction crystalline silicon devices are now approaching the theoretical limiting power efficiency of 33.7%, noted as the Shockley–Queisser limit in 1961. In the extreme, with an infinite number of layers, the corresponding limit is 86% using concentrated sunlight.

In September 2013, the solar cell achieved a new world record with 44.7 percent efficiency, as demonstrated by the German Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems. |

|

| |

Practical materials

The Shockley-Queisser limit for the theoretical maximum efficiency of a solar cell. Semiconductors with band gap between 1 and 1.5eV, or near-infrared light, have the greatest potential to form an efficient single-junction cell. (The efficiency "limit" shown here can be exceeded by multijunction solar cells.)Various materials display varying efficiencies and have varying costs. Materials for efficient solar cells must have characteristics matched to the spectrum of available light. Some cells are designed to efficiently convert wavelengths of solar light that reach the Earth surface. However, some solar cells are optimized for light absorption beyond Earth's atmosphere as well. Light absorbing materials can often be used in multiple physical configurations to take advantage of different light absorption and charge separation mechanisms.

Industrial photovoltaic solar cells are made of monocrystalline silicon, polycrystalline silicon, amorphous silicon, cadmium telluride or copper indium selenide/sulfide, or GaAs-based multijunction material systems.

Many currently available solar cells are made from bulk materials that are cut into wafers between 180 to 240 micrometers thick that are then processed like other semiconductors.

Crystalline silicon

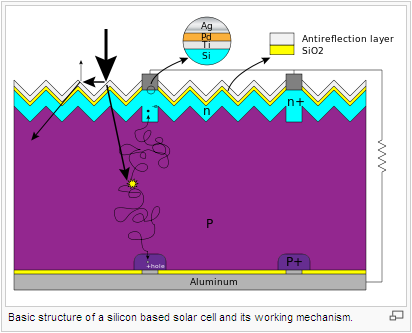

Basic structure of a silicon based solar cell and its working mechanism.By far, the most prevalent bulk material for solar cells is crystalline silicon (abbreviated as a group as c-Si), also known as "solar grade silicon". Bulk silicon is separated into multiple categories according to crystallinity and crystal size in the resulting ingot, ribbon, or wafer. These cells are entirely based around the concept of a p-n junction.

1.monocrystalline silicon (c-Si): often made using the Czochralski process. Single-crystal wafer cells tend to be expensive, and because they are cut from cylindrical ingots, do not completely cover a square solar cell module without a substantial waste of refined silicon. Hence most c-Si panels have uncovered gaps at the four corners of the cells.

2.polycrystalline silicon, or multicrystalline silicon, (poly-Si or mc-Si): made from cast square ingots — large blocks of molten silicon carefully cooled and solidified. Poly-Si cells are less expensive to produce than single crystal silicon cells, but are less efficient. United States Department of Energy data show that there were a higher number of polycrystalline sales than monocrystalline silicon sales.

3.ribbon silicon[28] is a type of polycrystalline silicon: it is formed by drawing flat thin films from molten silicon and results in a polycrystalline structure. These cells have lower efficiencies than poly-Si, but save on production costs due to a great reduction in silicon waste, as this approach does not require sawing from ingots.

4.mono-like-multi silicon: Developed in the 2000s and introduced commercially around 2009, mono-like-multi, or cast-mono, uses existing polycrystalline casting chambers with small "seeds" of mono material. The result is a bulk mono-like material with poly around the outsides. When sawn apart for processing, the inner sections are high-efficiency mono-like cells (but square instead of "clipped"), while the outer edges are sold off as conventional poly. The result is line that produces mono-like cells at poly-like prices.

Thin films

Thin-film technologies reduce the amount of material required in creating the active material of solar cell. Most thin film solar cells are sandwiched between two panes of glass to make a module. Since silicon solar panels only use one pane of glass, thin film panels are approximately twice as heavy as crystalline silicon panels, although they have a smaller ecological impact (determined from life cycle analysis).[30] The majority of film panels have significantly lower conversion efficiencies, lagging silicon by two to three percentage points.[31] Thin-film solar technologies have enjoyed large investment due to the success of First Solar and the largely unfulfilled promise of lower cost and flexibility compared to wafer silicon cells, but they have not become mainstream solar products due to their lower efficiency and corresponding larger area consumption per watt production. Cadmium telluride (CdTe), copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) and amorphous silicon (a-Si) are three thin-film technologies often used as outdoor photovoltaic solar power production. As of December 2013, CdTe was most cost effective (U.S. manufacturing cost per installed watt: $0.59 reported by First Solar) widely used thin film technology, and CIGS technology has the highest laboratory efficiency (20.4% as of December 2013), though CdTe cells made by First Solar have the highest industrial efficiency, and the lab efficiency of the immature GaAs thin film technology tops 28%.

Cadmium telluride

A cadmium telluride solar cell uses a cadmium telluride (CdTe) thin film, a semiconductor layer to absorb and convert sunlight into electricity. One disadvantage of this technology, the only thin film material so far to rival crystalline silicon in cost/watt, is that cadmium is a deadly poison. Another issue is that tellurium (anion: "telluride") is a metal extremely rare in the earth's crust, hence CdTe cells have no chance at a primary role in solving the question of fossil fuel replacement in the long term.

The cadmium present in the cells would be toxic if released. However, release is impossible during normal operation of the cells and is unlikely during fires in residential roofs. A square meter of CdTe contains approximately the same amount of Cd as a single C cell nickel-cadmium battery, in a more stable and less soluble form.

Copper indium gallium selenide

Copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) is a direct band gap material. It has the highest efficiency (~20%) among thin film materials (see CIGS solar cell). Traditional methods of fabrication involve vacuum processes including co-evaporation and sputtering. Recent developments at IBM and Nanosolar attempt to lower the cost by using non-vacuum solution processes.

GaAs thin film

The Dutch Radboud University Nijmegen set the record for thin film solar cell efficiency using a single junction GaAs to 25.8% in August 2008 using only 4 µm thick GaAs layer which can be transferred from a wafer base to glass or plastic film. Recently, this record has been increased to 28.8%. The high efficiency obtained in GaAs thin film solar cells is attributed to the extreme high quality GaAs epitaxial growth, surface passivation by the AlGaAs, and the promotion of photon recycling by the thin film design.

Silicon thin films

Silicon thin-film cells are mainly deposited by chemical vapor deposition (typically plasma-enhanced, PE-CVD) from silane gas and hydrogen gas. Depending on the deposition parameters, this can yield:

1.Amorphous silicon (a-Si or a-Si:H)

2.Protocrystalline silicon or

3.Nanocrystalline silicon (nc-Si or nc-Si:H), also called microcrystalline silicon.

It has been found that protocrystalline silicon with a low volume fraction of nanocrystalline silicon is optimal for high open circuit voltage. These types of silicon present dangling and twisted bonds, which results in deep defects (energy levels in the bandgap) as well as deformation of the valence and conduction bands (band tails). The solar cells made from these materials tend to have lower energy conversion efficiency than bulk silicon, but are also less expensive to produce. The quantum efficiency of thin film solar cells is also lower due to reduced number of collected charge carriers per incident photon.An amorphous silicon (a-Si) solar cell is made of amorphous or microcrystalline silicon and its basic electronic structure is the p-i-n junction. a-Si is attractive as a solar cell material because it is abundant and non-toxic (unlike its CdTe counterpart) and requires a low processing temperature, enabling production of devices to occur on flexible and low-cost substrates. As the amorphous structure has a higher absorption rate of light than crystalline cells, the complete light spectrum can be absorbed with a very thin layer of photo-electrically active material. A film only 1 micrometer thick can absorb 90% of the usable solar energy.[38] This reduced material requirement along with current technologies being capable of large-area deposition of a-Si, the scalability of this type of cell is high. However, because it is amorphous, it has high inherent disorder and dangling bonds, making it a bad conductor for charge carriers. These dangling bonds act as recombination centers that severely reduce the carrier lifetime and pin the Fermi level so that doping the material to n- or p- type is not possible. Amorphous Silicon also suffers from the Staebler-Wronski effect, which results in the efficiency of devices utilizing amorphous silicon dropping as the cell is exposed to light. The production of a-Si thin film solar cells uses glass as a substrate and deposits a very thin layer of silicon by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). A-Si manufacturers are working towards lower costs per watt and higher conversion efficiency with continuous research and development on multijunction solar cells for solar panels. Anwell Technologies Limited recently announced its target for multi-substrate-multi-chamber PECVD, to lower the cost to US $0.50 per watt.Amorphous silicon has a higher bandgap (1.7 eV) than crystalline silicon (c-Si) (1.1 eV), which means it absorbs the visible part of the solar spectrum more strongly than the infrared portion of the spectrum. As nc-Si has about the same bandgap as c-Si, the nc-Si and a-Si can advantageously be combined in thin layers, creating a layered cell called a tandem cell. The top cell in a-Si absorbs the visible light and leaves the infrared part of the spectrum for the bottom cell in nc-Si.Recently, solutions to overcome the limitations of thin-film crystalline silicon have been developed. Light trapping schemes where the weakly absorbed long wavelength light is obliquely coupled into the silicon and traverses the film several times can significantly enhance the absorption of sunlight in the thin silicon films. Minimizing the top contact coverage of the cell surface is another method for reducing optical losses; this approach simply aims at reducing the area that is covered over the cell to allow for maximum light input into the cell. Anti-reflective coatings can also be applied to create destructive interference within the cell. This can be done by modulating the refractive index of the surface coating; if destructive interference is achieved, there will be no reflective wave and thus all light will be transmitted into the semiconductor cell. Surface texturing is another option, but may be less viable because it also increases the manufacturing price. By applying a texture to the surface of the solar cell, the reflected light can be refracted into striking the surface again, thus reducing the overall light reflected out. Light trapping as another method allows for a decrease in overall thickness of the device; the path length that the light will travel is several times the actual device thickness. This can be achieved by adding a textured backreflector to the device as well as texturing the surface. If both front and rear surfaces of the device meet this criterion, the light will be 'trapped' by not having an immediate pathway out of the device due to internal reflections. Thermal processing techniques can significantly enhance the crystal quality of the silicon and thereby lead to higher efficiencies of the final solar cells.[41] Further advancement into geometric considerations of building devices can exploit the dimensionality of nanomaterials. Creating large, parallel nanowire arrays enables long absorption lengths along the length of the wire while still maintaining short minority carrier diffusion lengths along the radial direction. Adding nanoparticles between the nanowires will allow for conduction through the device. Because of the natural geometry of these arrays, a textured surface will naturally form which allows for even more light to be trapped. A further advantage of this geometry is that these types of devices require about 100 times less material than conventional wafer-based devices.

Multijunction cells

High-efficiency multijunction cells were originally developed for special applications such as satellites and space exploration, but are also now used effectively with terrestrial solar concentrators. Multijunction cells consist of multiple thin films, each essentially a solar cell in its own right, grown on top of each other, typically using metalorganic vapour phase epitaxy. A triple-junction cell, for example, may consist of the semiconductors: GaAs, Ge, and GaInP2.[42] Each type of semiconductor will have a characteristic band gap energy which, loosely speaking, causes it to absorb light most efficiently at a certain color, or more precisely, to absorb electromagnetic radiation over a portion of the spectrum. Combinations of semiconductors are carefully chosen to efficiently absorb most of the solar spectrum, thus generating electricity from as much of the solar energy as possible.GaAs based multijunction devices are the most efficient solar cells to date. In October 15, 2012, triple junction metamorphic cell reached a record high of 44%.Tandem solar cells based on monolithic, series connected, gallium indium phosphide (GaInP), gallium arsenide GaAs, and germanium Ge p–n junctions, are seeing demand rapidly rise. Between December 2006 and December 2007, the cost of 4N gallium metal rose from about $350 per kg to $680 per kg. Additionally, germanium metal prices have risen substantially to $1000–1200 per kg this year. Those materials include gallium (4N, 6N and 7N Ga), arsenic (4N, 6N and 7N) and germanium, pyrolitic boron nitride (pBN) crucibles for growing crystals, and boron oxide, these products are critical to the entire substrate manufacturing industry.Triple-junction GaAs solar cells were also being used as the power source of the Dutch four-time World Solar Challenge winners Nuna in 2003, 2005 and 2007, and also by the Dutch solar cars Solutra (2005), Twente One (2007) and 21Revolution (2009).

Emerging research topics and pre-industrial technology

Light-absorbing dyes (DSSC)

Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) are made of low-cost materials and do not need elaborate equipment to manufacture, so they can be made in a DIY fashion, possibly allowing players to produce more of this type of solar cell than others. In bulk it should be significantly less expensive than older solid-state cell designs. DSSC's can be engineered into flexible sheets, and although its conversion efficiency is less than the best thin film cells, its price/performance ratio should be high enough to allow them to compete with fossil fuel electrical generation.

Typically a ruthenium metalorganic dye (Ru-centered) is used as a monolayer of light-absorbing material. The dye-sensitized solar cell depends on a mesoporous layer of nanoparticulate titanium dioxide to greatly amplify the surface area (200–300 m2/g TiO2, as compared to approximately 10 m2/g of flat single crystal). The photogenerated electrons from the light absorbing dye are passed on to the n-type TiO2, and the holes are absorbed by an electrolyte on the other side of the dye. The circuit is completed by a redox couple in the electrolyte, which can be liquid or solid. This type of cell allows a more flexible use of materials, and is typically manufactured by screen printing or use of ultrasonic nozzles, with the potential for lower processing costs than those used for bulk solar cells. However, the dyes in these cells also suffer from degradation under heat and UV light, and the cell casing is difficult to seal due to the solvents used in assembly. In spite of the above, this is a popular emerging technology with some commercial impact forecast within this decade. The first commercial shipment of DSSC solar modules occurred in July 2009 from G24i Innovations.

Quantum dot solar cells (QDSCs)

Quantum dot solar cells (QDSCs) are based on the Gratzel cell, or dye-sensitized solar cell, architecture but employ low band gap semiconductor nanoparticles, fabricated with such small crystallite sizes that they form quantum dots (such as CdS, CdSe, Sb2S3, PbS, etc.), instead of organic or organometallic dyes as light absorbers. Quantum dots (QDs) have attracted much interest because of their unique properties. Their size quantization allows for the band gap to be tuned by simply changing particle size. They also have high extinction coefficients, and have shown the possibility of multiple exciton generation.

In a QDSC, a mesoporous layer of titanium dioxide nanoparticles forms the backbone of the cell, much like in a DSSC. This TiO2 layer can then be made photoactive by coating with semiconductor quantum dots using chemical bath deposition, electrophoretic deposition, or successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction. The electrical circuit is then completed through the use of a liquid or solid redox couple. During the last 3–4 years, the efficiency of QDSCs has increased rapidly with efficiencies over 5% shown for both liquid-junction and solid state cells. In an effort to decrease production costs of these devices, the Prashant Kamat research group recently demonstrated a solar paint made with TiO2 and CdSe that can be applied using a one-step method to any conductive surface and have shown efficiencies over 1%.

Organic/polymer solar cells

Organic solar cells are a relatively novel technology, yet may hold the promise of a substantial price reduction. These cells can be processed from liquid solution, hence the possibility of a simple roll-to-roll printing process, potentially leading to inexpensive, large scale production. In addition, these cells could be beneficial for some applications where mechanical flexibility and disposability are important. Current cell efficiencies are, however, very low, and practical devices are essentially non-existent.

Organic solar cells and polymer solar cells are built from thin films (typically 100 nm) of organic semiconductors including polymers, such as polyphenylene vinylene and small-molecule compounds like copper phthalocyanine (a blue or green organic pigment) and carbon fullerenes and fullerene derivatives such as PCBM. Energy conversion efficiencies achieved to date using conductive polymers are very low compared to inorganic materials. However, recent improvements have led to a NREL (National Renewable Energy Laboratory) certified efficiency of 8.3% for the Konarka Power Plastic, and organic tandem cells in 2012 reached 11.1%.

The active region of an organic device consists of two materials, one which acts as an electron donor and the other as an acceptor. When a photon is converted into an electron hole pair, typically in the donor material, distinct from most other solar cell types, the charges tend to remain bound in the form of an exciton, and are separated when the exciton diffuses to the donor-acceptor interface. The short exciton diffusion lengths of most polymer systems tend to limit the efficiency of such devices. Nanostructured interfaces, sometimes in the form of bulk heterojunctions, can improve performance.

In 2011, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Michigan State University developed the first highly efficient transparent solar cells that had a power efficiency close to 2% with a transparency to the human eye greater than 65%, achieved by selectively absorbing the ultraviolet and near-infrared parts of the spectrum with small-molecule compounds. Researchers at UCLA more recently developed an analogous polymer solar cell, following the same approach, that is 70% transparent and has a 4% power conversion efficiency. The efficiency limits of both opaque and transparent organic solar cells were recently outlined These lightweight, flexible cells can be produced in bulk at a low cost, and could be used to create power generating windows. In 2013, researchers announced polymer cells with some 3% efficiency. They used block copolymers, self-assembling organic materials that arrange themselves into distinct layers. The research focused on P3HT-b-PFTBT that separates into bands some 16 nanometers wide.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

|